Publisher Speak Keynote

Ian Mulvany — May 2025

Slides and annotations from my keynote at Publisher Speak

These are the slides from a keynote that I gave in May 2025 at Publisher Speak.

Back in January I wrote a somewhat tongue-in-cheek blog post about things that might be true about scholarly publishing -- https://world.hey.com/ian.mulvany/what-things-might-be-true-about-scholarly-publishing-11d227f3, and since then I've been looking to find some time to create a more constructive and positive overview of my thoughts. This talk was a great opportunity to do that.

Having worked for about twenty years in the field I decided to take a slightly more reflective stance. I used Simon Willison's tool for annotating slides to put this post together - https://simonwillison.net/2023/Aug/6/annotated-presentations/.

The topic of the talk is about the future. I don't think there is anything unique or novel in this talk, but I really wanted to get across my enthusiasm for the opportunities ahead of us.

(As a side note, I used GenAI for a lot of the visuals in this presentation, for which I am absolutely unapologetic, it saved me a ton of time).

Much of the thinking behind this talk is inspired by the following three sources.

I've seen The Knowledge Machine by Michael Strevens - https://www.strevens.org/scientia/- described as a modern classic in the making, and I fully agree, it's the best book I've read on how science works, it has deeply informed my thinking and I go into the main arguments in this talk.

Large AI models are cultural and social technologies - https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt9819 - by Farrell et. al. provides a good dose of sanity about what LLMs are, or are not, and the framing here applies equally as well to science.

The two reports on Identity in publishing by STM are fantastic, clearly written and this work is important and vital to our industry - https://stm-assoc.org/new-stm-report-trusted-identity-in-academic-publishing/.

The talk is quite long, so I wanted to get the key takeaway messages out at the very start.

My first framing position is that the future is entirely open, entirely ahead of us, and we are in a consequential moment in the history of research.

What we do now really matters, we can play an important role in the future of scholarship, the future of science.

The main things I want people to take away from today are the following (if they have to pick just one thing to do, pick one of these).

- Strongly support data and code sharing as part of the scholarly record.

- Take identity much more seriously than we have in the past.

- Integrate with ORCID trust markers.

I think the need for supporting data, and the usefulness of ORCID, are well understood by our industry, so I'm going to be spending most of this talk focusing on identity as I think that's an area that needs a lot more attention.

But on data I want to give a shout out to https://datadryad.org which is a community-run open infrastructure for publishing and curating research data. I've been on the board of Dryad for a number of years. Simply - authors can publish their data, and have it curated. It's a good example of a neutral piece of infrastructure that can support any field.

https://orcid.org/ should be well known in our industry. ORCID has supported trust markers since 2021. These allow trusted institutions to add assertions onto the record of an individual. It's a way to do what it says on the tin - create a record of trusted assertions. We will come back to this idea later. (https://world.hey.com/ian.mulvany/orcid-trust-markers-70e53877)

I want to talk today about what we do as an industry, and perhaps point a little to ways of thinking about what we should be doing in the future.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is often asked the question - what does he think will be different in the future, and his answer is that we shouldn't think so much about what will change, but more about what won't change.

Those are the things that you can continue to build value around. In Amazon's case that was about increasing choice for customers, and driving prices down.

I'm going to talk about what I think really matters in research, and what we have to do as an industry to support that. I think a lot of the forms of how we support research are up for grabs, and I think there is a lot of opportunity in how we design and deliver services, but I think in the long term the fundamentals will remain in place.

Now of course there are things that are changing

- The locus of where political pressure is being exerted.

- The change in our experience of time that AI is giving us.

- Scale that is making some of the assumptions that we had been working under before untenable.

But how do we get to a view of what those things are that might stay the same?

For an answer to that question I'm going to draw on this work. This is a specific and fairly opinionated view on how science works, building on top of the works of Popper and Kuhn. I acknowledge that you might not agree with everything presented by Strevens, but I think it's really worth engaging with.

At the heart of his thesis are two key ideas - the iron rule of evidence, and how evidence converges to an agreed view - what he calls Baconian Convergence.

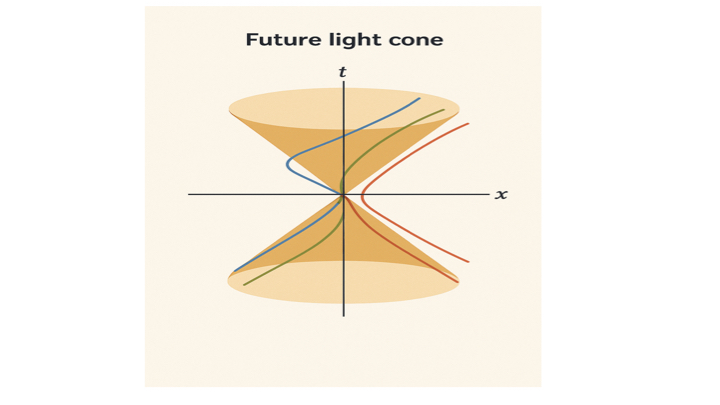

The mental model that I like is of all of human knowledge being something like a sphere.

I like to think that our knowledge of the world grows over time.

But if we zoom right in to the surface of the sphere it's kind of spiky. These spikes are where researchers are pushing our boundaries of knowledge forward. If you are working at the tip of one field you might as well be almost disconnected from the tip of another field.

The Iron Rule states that the only permissible move, when working at the cutting edge of science, is to tie your public claims about the world to observable evidence. This is the only thing that you are allowed to publish, you can't publish hypotheticals, or lay claims to other sources of validation for your claims (e.g. beauty or harmony).

While this sounds obvious because we are all used to the process of science today, Interestingly Strevens says that this is actually a deeply irrational and un-human-like way to behave.

Baconian convergence then happens when we have data that is initially unclear, but over time becomes resolved to one side of an argument, or another.

There are some other interesting by-products of this structure.

One of these is that it can make cross-discipline work very difficult. The sub-norms that emerge in one particular field can make it hard to bring in claims from another field, and by the time claims become normalized as part of the common set of knowledge that we have, fields will have moved on.

Another interesting aspect of this is that if you are at the tip of one of these fields you may well know all of the other key researchers working in your area. You may, in fact, believe that there might be no need for journals, or for peer review, as you are working within a shared context of what is known and what is accepted. (I'll come back to this again later).

So the Iron Rule, and Baconian convergence are the mechanisms that drive science forward, but there are supporting tacit norms that are needed too.

A lot of the work to push the boundary of knowledge is hard, thankless. It takes a lot of sacrifice, so you need to have competitive people engaged in this.

For that to work you need to have the right level of accreditation. There has to be some form of reward in place.

It's also important to recognize that this process is done by humans, with all of the failings and frailties that this brings. How folk behave in private, and the claims they make in informal spaces, can be, and will be, different from the publicly posted claims in the scientific record - according to this iron rule.

Lastly Strevens says that an important key factor is to not change this system too much. It does not need to suffer from over-optimization.

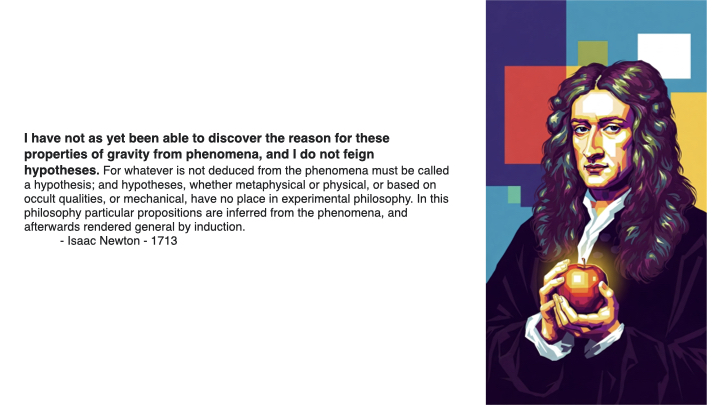

I think one of the more contestable points made in the book is that this system originated in the middle of the 17th century. I acknowledge that this could be a point of debate, but I am persuaded (and that might be due to my own background as an astrophysicist).

The claim here is that when Newton published results that stood purely on their observational power, and not grounded from any other type of rational argument, led to the birth of the Iron rule.

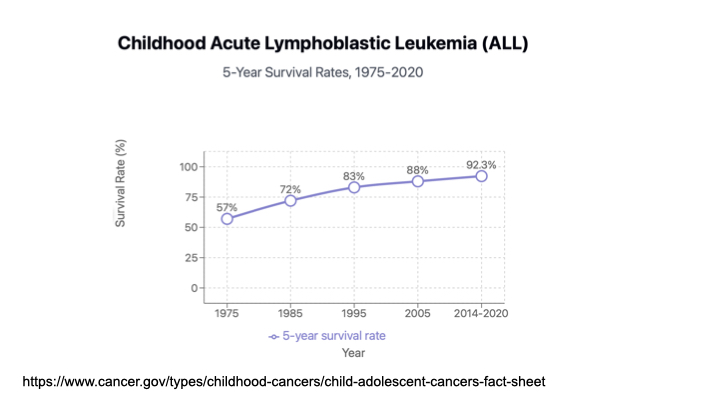

This in turn laid the foundation for a modern science that has been remarkably effective.

To put that into context, the claim here is that we have only been doing modern science for a few hundred years. This is a blink of an eye in human history.

We have only had between twelve and fourteen generations of people doing science as we know it.

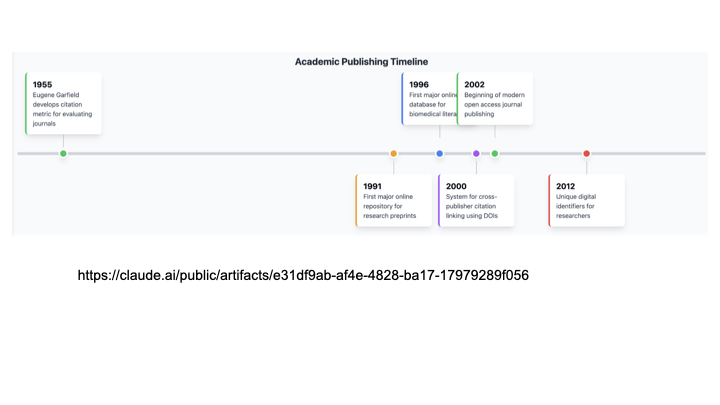

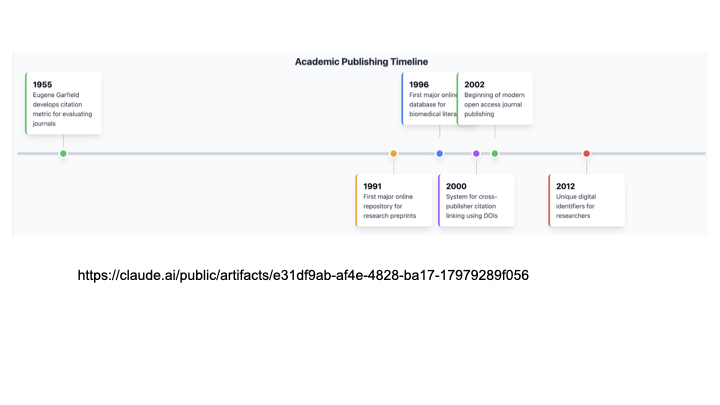

If we zoom in a bit more the amount of time that we have been doing web-enabled science is even shorter, on the timeline of research what is now core infrastructure such as DOIs and ORCIDs have been around for hardly any time at all.

One of the characteristics of this system that we have is that it works in an accretive way. Findings build over time. There are rarely silver bullet discoveries, but when there are, overall, the long game is more effective.

It's also true that the world we are in, the facts of the world we are in, have no consideration for us. The facts of the world don't shape themselves for us, or for our convenience. That's why the Iron rule is so important.

With all that in mind, I want to come back to the question I posed, what might stay the same in the long run?

These are my bets:

- We need to connect claims to evidence, but maybe we don't need only journal articles.

- The process will remain messy and human, and be open to all of the pressures that ensue.

- Rewards of some kind will be needed.

- We need to take care of this system.

It's a socio-technical system. Drawing from this paper - https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.adt9819 these are "systems or tools that enable humans to access, process, reorganize, transform, and restructure information accumulated by other humans, facilitating large-scale coordination within society."

Large AI models are also cultural and social technologies.

We rely on social institutions (markets, democracies, bureaucracies) to coordinate information/decision-making. These can be thought of as technologies.

These systems often use lossy representations of the state of affairs, but they are useful representations (price mechanism, election results, GDP, bureaucratic categories)

The publishing ecosystem operates on a level of abstraction a few steps away from the underlying reality and so the way we interact with the core content -- through the processes that we have created -- loses some details as you get more removed from the immediacy of the experiments.

These systems tend to lead to the emergence of institutions (normative, regulatory, editors, peer review, libel laws, election law, etc.) to temper effects.

Our institutions need to evolve as we have to operate with more scale.

LLMs generate new possibilities for recombining information and coordinating actions at scale.

Example socio-technical systems:

- Pictures

- Writing

- Video

- Internet search

- Economic markets

- State bureaucracies

- Representative democracies

- Spoken language

- Libraries

- Newspapers

- Wikipedia

Example Institutions that emerged:

- Editors

- Peer review

- Libel laws

- Election law

- Deposit insurance

- Securities and Exchange Commission

So far I've talked about our current structure of science. It's one example of a socio-technical system with the strong and somewhat unique characteristic of this iron rule. (It would be all too easy to imagine us losing this iron rule).

There are a couple of attributes of this system that I want to mention before moving on.

We can kind of proxy the number of spikes on the surface of human knowledge with the number of journals that exist, about 35K at this point in time, five to seven million contributions at those endpoint per year, kind of.

It is probably true that most science that is done is in the more normal range, filling in details, being a vehicle to support careers, not so much at the very sharp points of uncertainty.

But we also don't know the following:

- We don't know ahead of time what area of basic research will result in a significant breakthrough for society.

- We don't know ahead of time how long it will take for any piece of basic research to have that societal impact.

- We can't tell ahead of time at what point in their career an academic will enter their "hot phase" where their work is really meaningful.

And we do know:

- The world is filled with complexity and detail, beyond our full ability to map it all.

- If we overly concentrate lines of attack (funding too similar groups) we get worse results than if that funding is spread across more diverse bets.

This is encapsulated really nicely by a law derived by Ross Ashby in 1956 - "Ashby's law of requisite variety"

He was studying how many degrees of freedom you need in a system to operate effectively.

What his analysis found is that any system needs to have as many degrees of freedom as the environment it is operating in to be effective.

That means when we are looking at complex systems we need to have a lot of complexity. We need lots of different viewpoints on our world in order to be able to understand our world effectively.

I think it's an interesting challenge that we have as an industry. We all want to demonstrate impact, to create real value, and yet the timeline for the outcome of science to create that impact is uncertain, but almost certainly longer than a single funding round from a grant call, or any single initiative that we might invest in.

And yet by our very nature, we are compelled to try to make improvements.

I think a lot of the initiatives in our industry are attempts to break through that constraint. I think what we do is better as a result of these things, and in each case, there have been periods of figuring things out. We can certainly get very caught up in these initiatives.

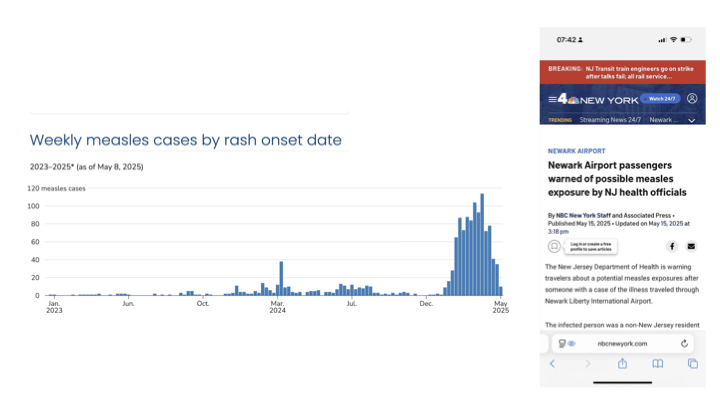

The key one right now is research integrity.

But I want us to always think about that slow steady improvement that is the result of research, and when thinking about it that way I think two things we should always be striving for are creating the highest quality scholarly record that we can, and reducing the pain and cost for individuals in participating in this activity (that could be actual cost, or cost in time, or cost in complexity).

We have a problem though ...

That timeline of science is so short, and we really only have had one generation, maybe two, doing web-enabled science. The coming generation will be doing AI-enabled science!

And yet we are operating with some of the rules of science from the 17th century. Our scale of operation has increased, but we have not sufficiently updated the mechanisms of our institution to accommodate for that scale change.

And I would say that as we think about the changes we must make we have to be careful about the decisions we make. Those decisions will have consequences that will echo into the future.

Getting to the web early has been a huge success for scholarship. At the time XML seemed like a good idea, but now most people building infrastructure are trying to build away from that decision, and it's really hard.

The APC seemed like a good reasonably transparent decision for creating a functioning business model around open access, but it has led to concerns about barriers to publishing, and to a large amount of complexity in how transactions are managed.

And impact factor has been used a lot more than the creators of it thought it would. It has actively changed research behavior by accidentally being the reward mechanism for research.

We are now faced with a new set of decision points, and the decisions we make over the next few years will have consequences for a long time into the future (so no pressure!).

I'm going to focus the rest of my talk on identity because I think it's the area that best represents one of our structural weaknesses, while at the same time being addressable, and being an area that has a moral imperative connected to it.

But first I'm going to start with a somewhat amusing anecdote that is emerging just to show how slippery the concept of identity is in today's world.

Tech companies are starting to see an odd pattern in hiring. A CV will come in for a remote development position, claiming to be a candidate in Eastern Europe, or some rural part of North America. When the candidate is being interviewed online they are military-age Korean. They pass the technical interview with flying colors.

The reason for this is that they are North Korean military, and they are supported by an entire team behind them. They often actually turn out to be one of the best performers in the company because you have not just hired one person, but a whole team!

In this case, our assumptions about what was going on in the interview process don't match what was going on in reality.

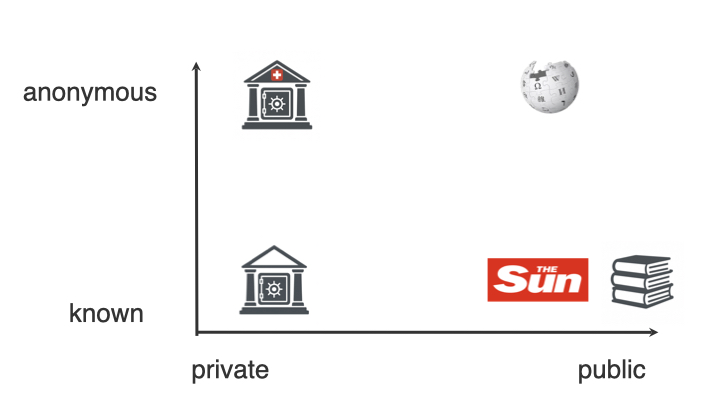

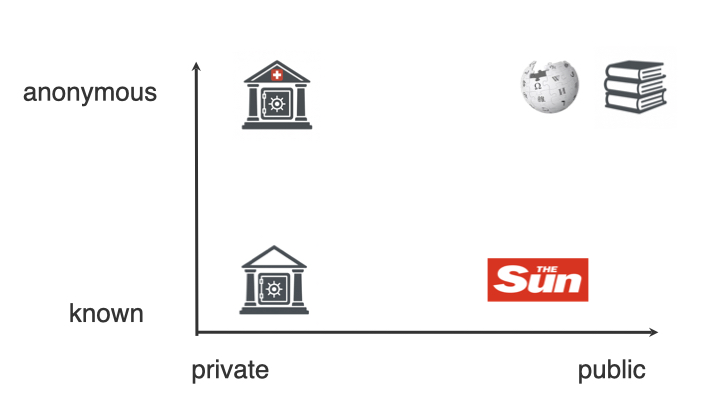

We have traditionally operated under the assumption in this picture, where academic works are public, and the authors of those works are known, much like work published in newspapers and other media.

If you know the people writing for you, you kind of don't need a 3rd party check on their identity.

The media stands by their bylines, and so know who is writing for them. That writing is public.

Banking is a great example of where high trust is needed - for the most part - so banks can put in place high barriers in terms of identity checks. They won't necessarily know the customer before conducting these checks.

The Swiss banking system manages to be both private and anonymous, and Wikipedia manages to be public and anonymous.

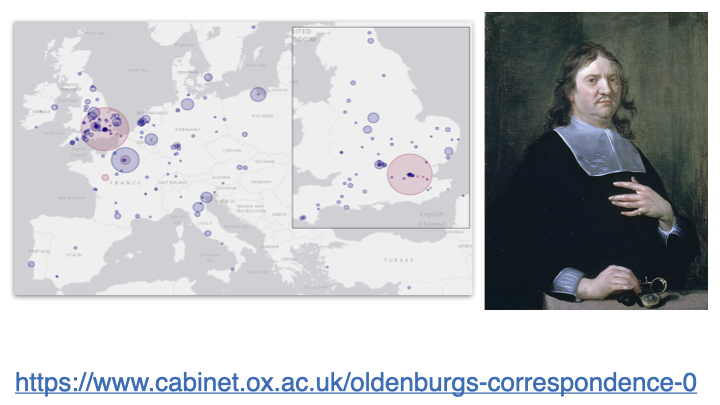

Our current assumptions about identity in research are derived directly from when science was done by small world networks. Shown here is the map of correspondence from Henry Oldenburg, the first secretary of the Royal Society. At that time people just knew each other.

But that assumption does not hold up anymore within science.

We now have to treat authors as anonymous because of the scale of publishing today. With the volume of papers being published, and across so many journals, even with well-connected editors, there will just be too many papers being submitted.

Unlike with mainstream media, we invite contributions ideally from anyone anywhere in the world, and we want to continue to be able to do that in light of the law of requisite variety.

Wikipedia manages to make this work through being built on top of a single centralized digital platform that can engineer social software to manage bad actors. Wikipedia sometimes describes themselves as the truth infrastructure of the web, and that is what scholarly publishing needs to support too, but our current norms and infrastructure do not meet that demand today.

There are other structural weaknesses that represent attack vectors too. I've already described how social technologies in a way summarize information for us. Our shorthand for a scholarly work is the form of the work. This was pointed out years ago by Geoffrey Bilder and he showed this slide and asked the audience to name the parts that are blacked out. Because you can all identify where the title, abstract, citations, author lists go, this means when you are presented with something that looks like this it takes on the mantle of feeling scholarly. That is one of the things that makes paper mills work so well; we are so tied to the form of the scholarly record that our system can easily be fooled by form.

We need to make change.

I'm now going to walk through, at a very high level, some of the key recommendations in the report "Trusted Identity in Academic Publishing - STM report". - https://stm-assoc.org/new-stm-report-trusted-identity-in-academic-publishing/.

This is a fantastic report, and while it leaves many questions open, I cannot recommend it highly enough. This is important work that our industry needs to engage in.

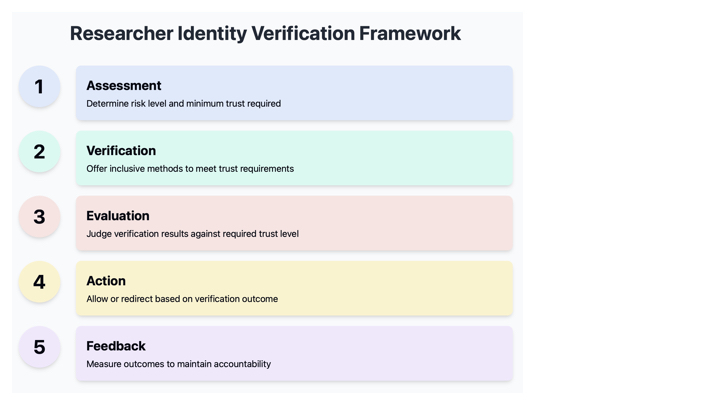

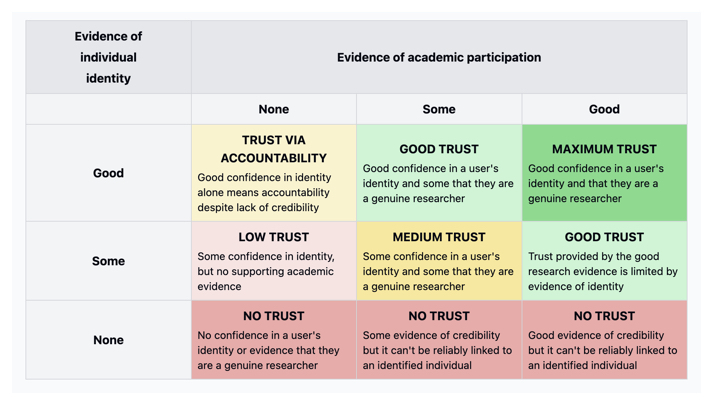

At the heart of the report is the idea that we need to move beyond a single-dimensional view of identity verification.

That will mean adding more complexity into our systems, and that will mean new sets of trade-offs, so we will need to engage in this work.

There is a lot of detail in the following slides, so my intention is to use these to give you a flavor of what the report recommends, rather than walking through all of them in detail.

The authors call out the importance of having a feedback loop in place as we engage with any changes to our current systems around identity, but crucially the report starts out by recognizing that in our field, unlike fields where strong know-your-customer protocols are fine - it is important that we retain as open a system as possible to allow as many voices as possible to be heard in the scholarly record.

They are also very clear to call out that trust in the claims being made is distinct from trust in the identity of those making the claims.

They also think in the report a lot about the many parameters and failure modes that might surround identity checks, e.g. a specific verification method that might be preferred by a funder or journal, might not be available to an individual.

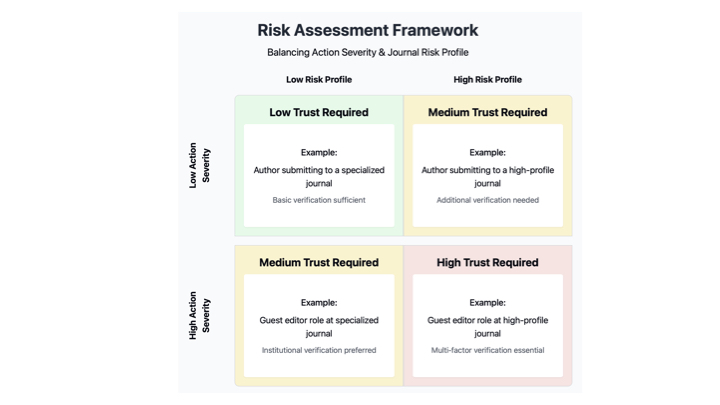

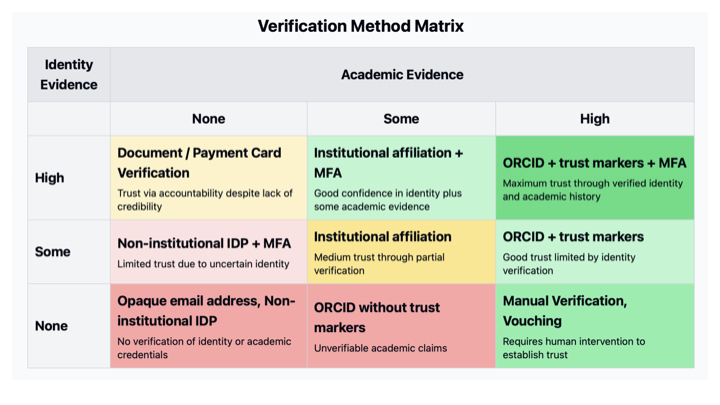

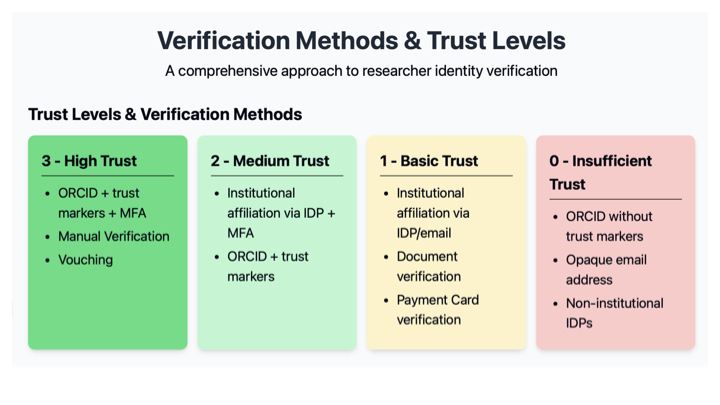

The next key idea presented is we need to balance the level of trust required with the potential for harm from a role or action. Not all roles are equally risky. We need a higher bar of trust for roles that could do more harm, e.g. managing editors, folks managing our systems.

Equally some kinds of evidence about the person are going to be more useful. The more academic the evidence e.g. having a verification from a trusted institution, the better.

That framework of assessing the level of academic participation can be mapped directly onto systems that are in play today, from ORCID trust markers through to manually verifying the identity of an individual.

What is important here is that we might choose to apply different levels of trust or verification based on the combined picture of what information we already have about an individual and what level of risk they may pose in a particular moment given the action they are being asked to do.

At any point through their journey we could define the level of trust that they have, given the information that we have about them.

They end with a good overview of some of the challenges that need to be addressed.

In particular I want to call out that no system will remove all bad actors. Also, trust is not absolute; it will vary over time. That can play both ways, for example, if someone is in good standing then for the next few times that they are operating in the system, they should encounter an easier path, and if that information could be distributed to all the parties, so much the better.

I see some additional issues that were not called out so much in the report. Three that I want to highlight are:

- How do we get to a norm around what level of trust is enough? The pressure of delivering publications on a daily basis will mean that our staff and systems will want effectively a binary decision, when everything we have been saying here so far has been about introducing more nuance, not less.

- Any change to our systems will require some level of software changes, and these are challenging in a distributed industry. We are going to need the initial experiments around these ideas led by key vendors in the field.

- We are certainly not going to get a lot of this stuff right initially, so how might we create conditions where we can fail gracefully in ways that minimize the risk and harm to authors?

I think a lot of it will come down to fora like this one, and a shared intent to tackle these issues.

I'm going to close out the discussion on identity. There are many really great initiatives looking at questions around trust; if you don't know about the following they are worth checking out (and these are by no means exhaustive)

PKP Fact Labels

STM integrity hub

ORCID Trust Markers

RICS from MPS

Dryad

Democratizing Data

OpenCitations

openRxiv

Open Science Indicators

In the last few moments, turn to offering a more expansive vision of the opportunity that lies in front of us.

I want to come back to this picture for a moment. Each branch of research is isolated in some way from other branches, through specialization.

They are also, to a certain extent isolated from parts of their past through the window of attention that any researcher can carry.

But all of that knowledge is now digitized, and we now have tools that can appear to be able to reason over context in much larger windows than we can.

We should be able to, we must, look to build context engines that give more power to those working at the cutting edge, that can build connections that might be invisible to us, and that can connect us more deeply to past findings that might have dropped out of sight ever so momentarily.

A high trust corpus is paramount in realizing that vision, and having LLMs that play by the rules of the game is equally important.

As we think about building features, or patterns of engagement with our communities, I believe we need to think about how we can build more context into those systems.

I hope I have left you with some things to consider. If you are looking for very specific things to do I again urge you to look at supporting data publishing, take identity seriously, and explore ORCID trust markers.

My closing thought.

We have had the process of rational inquiry, of natural philosophy, for only the blink of an eye.

We have had web-enabled science for even less time.

And yet the future lies in front of us, as yet unmade.

The decisions you make can shape that future. You have significant opportunity to build great things that will compound over time.

Thank you.